Best Local Album

The Postmarks

More than two years of fine-tuning and detail work went into creating this slice of mopey melancholy, and the results speak for themselves. Charting overseas and winning plenty of domestic college-radio airplay upon its February 2007 release, The Postmarks bore as much resemblance to a lowly local release as a cello does to a kazoo. Due to the perfectionism of bandleader and multi-instrumentalist Christopher Moll, every moment of this multitracked tapestry has been polished to within an inch of its life, with ear-pleasing results. Plus, when was the last time a local record was fortified with glockenspiel? Timpani? French horn? An entire string section?! All of which was impressive enough to curry the favor of Adam Schlesinger (Fountains of Wayne) and Andy Chase (Ivy), who produced the record. South Florida hasn't exactly been a hothouse nurturing the darling buds of pure pop perfection, but the Postmarks have at least laid the groundwork here. Yes, The Postmarks is delicate, fragile, sort of sad, and twee as all get-out, but damned if it isn't the most affecting collection of songs to come from this peninsula tip in a long, long time. Enjoy while gazing out a raindrop-covered window for maximum effect. Absinthe optional.

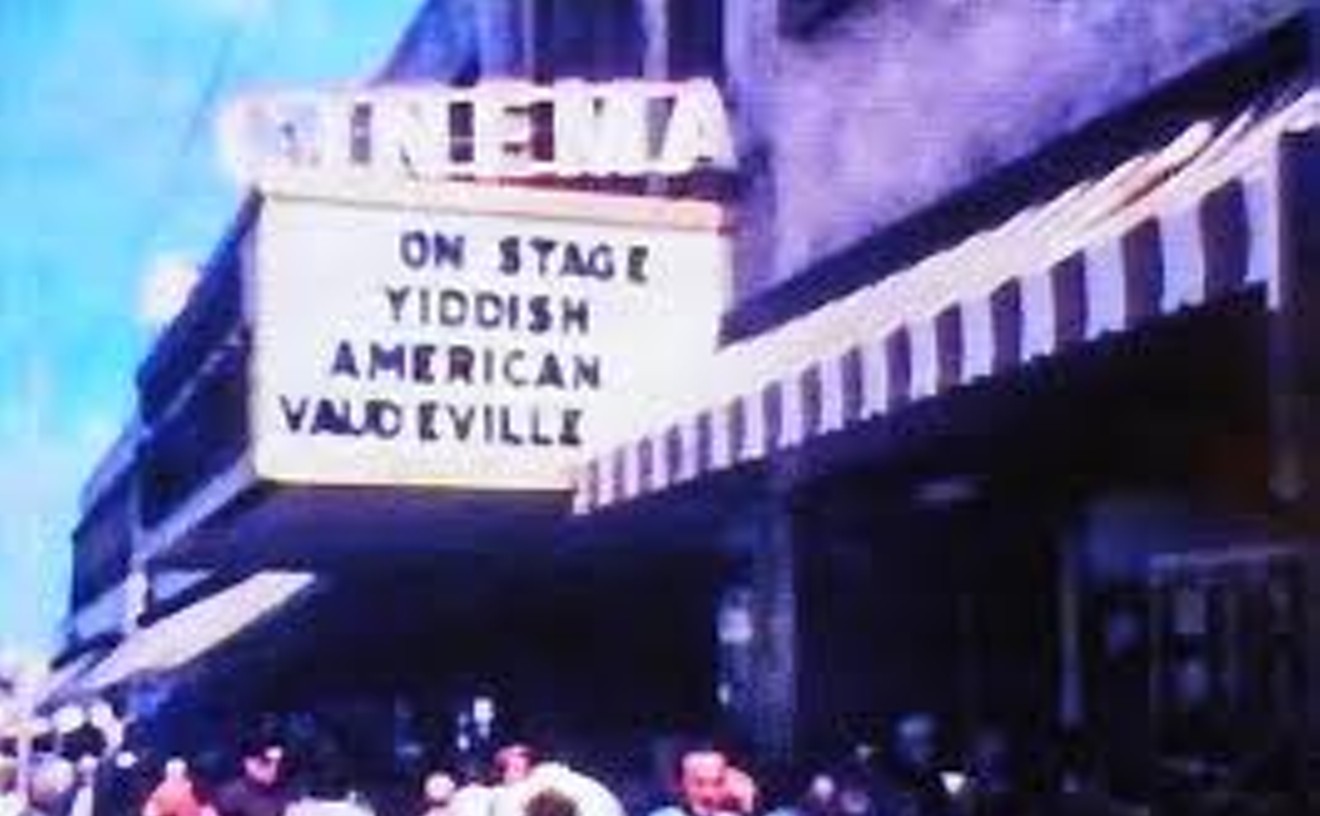

Best MusicVenue

Club Cinema

Our inaccessible geography aside, one major reason bands have forsaken us is our preponderance of pathetic venues with nasty bathrooms, bad sound, no parking, and just a general all-around malaise. Part of the problem is that few live music venues were designed as such — believe it or not, we've had everything from Cuban restaurants to Winn-Dixies doubling as rock-concert rooms. Naturally, like everything else in South Florida, Club Cinema is housed in a strip mall. But inside, the swankier-than-thou feel echoes famous rooms like the Fillmore. The lighting, the design, and the well-placed bars all signify class and attention to detail. Now, in these very pages, we've dismantled local politicians and exposed Club Cinema as a business that's very likely more mobbed-up than a Godfather-Goodfellas marathon. But what the heck — if that's what it takes to make audiences feel like they're watching a show in a real goddamned city, we'll take it.

- 3251 N. Federal Highway, Lighthouse Point, 33064 Map

- 954-785-5225

- clubcinema.electrostub.com

Best Band to Break Up in the Past 12 Months

Die Stinkin'

This punk-rock band's members ranged in age from "barely old enough to drink" to "nearing retirement," but they all had a natural don't-give-a-fuck attitude that reminded you of your favorite group of high school misfits who just got a license but couldn't afford a car. So when they broke up last year, it was like losing a first love. They were the unifiers who kept the rest of us young, and their equal-opportunity disdain for anything mature was as infectious as their three-chord melodies. Fortunately for all involved, the boys of Stink started seeing one another again in secret — a small benefit show here, a warehouse show there — until they finally reunited. Who knows how long it'll last, so enjoy it while you can.

Best Metal Band

Torche

Modern metal is the new indie rock, let's just get that straight. Everyone has now officially traded in his Clairol black hair dye for a long, flowy metal mane. And despite this flooded market of mediocre metal, Fort Lauderdale is able to boast a band that was there all along, developing its musical identity, getting famous, and influencing this new generation of head bangers. May we present Torche. Exhumed from the ashes of Floor and Cavity, this four-piece produces an amazingly surreal take on stoner sledge metal. Vocal harmonies bind with slow-driving guitar riffs, while loosely tuned bass strings flail deep into the lowest sonic registers. Despite how much media hype surrounds this band, every time it returns home, it gets back to its roots, trading in larger, out-of-town venues for teenagers' house parties and small clubs like the Billabong. The boys of Torche embrace the energy produced at these shows and flip their hair in time with the music — along with the hundreds of smiling, jam-packed fans. Sabbath would be so proud.

Best Theatrical Production

The Faith Healer Inside Out Theatre

It's not easy to draw out a moment of suspense — those instants when it's certain that something revelatory or horrifying is about to happen. In The Faith Healer, such a moment was drawn out for two hours. Barely a story, The Faith Healer, by playwright Brian Friel, is comprised of four monologues from three people — faith healer Francis Hardy (Stephen J. Anthony); his mistress, Grace (Sandra Ives); and his manager, Ted (Ken Clement) — recounting, in fragments, their two decades traversing the British Isles, healing or failing to heal as they went. What went wrong remains unclear, baffling even to those who were there. All they know is that, through some small accumulation of real or imagined betrayals, their journey destroyed them and in some way forced them to destroy one another. As the three actors tried to explain themselves, suffocated beneath the dead weight of memory, you wondered if the mysterious forces that acted upon them might not be present in the theater, ready to act upon everyone — and whether anyone would recognize such forces if they appeared.

Best Director

Kim St. Leon for The Faith Healer at Inside Out Theatre

Good directing is like alchemy: It is the trick of taking disparate, unknown elements and fusing them into a whole that not only makes sense but equals more than the sum of its parts. Kim St. Leon did this as well as it's ever been done with Inside Out Theatre's production of The Faith Healer. She had help, obviously — three actors who saw straight through to the soul of the piece — but she's the one who must be credited with the bravery and smarts it required to stake her production's success on the small clutch of intangibles allowed her in the story's anti-narrative. It was the way a pedestrian anecdote was made to seem monstrous through a slight change in Sandra Ives' vocal timbre or the way the slow lift of Loreena McKennit's cheesy synth-Celt muzak framed the last scene, when Stephen J. Anthony's titular faith healer was ready to ascend into heaven but looked ready to burst into flames. An event like St. Leon's The Faith Healer is something akin to a vision: both impossible to deny and impossible to explain. The great mystery isn't what it meant but how she managed to explain it to the actors in the first place.

If you saw Glengarry's original production or the 1992 film adaptation, you inevitably compared Paul Tei's fast-talking, gel-haired Ricky Roma to the interpretations by a young Joe Mantegna or middle-period Al Pacino. Miraculously, in spite of this heavyweight company, Tei suffered not at all from the comparisons. From his first scene, he came on like a cross between John Travolta and Satan — utterly amoral but unflaggingly sweet, too cool to let anything under his skin and too driven to allow anything to deter him from his purpose. When at last something did rankle him, watching the subsequent blowout was akin to looking out the rear window of the Enola Gay. In one of the dirtiest and most flagrantly outlandish roles brought to life on any Florida stage this season, Tei created one of the most complete, naturalistic, and straight-up entertaining portraits anybody's ever seen.

Taking on the role of Eleanor of Aquitaine in Caldwell's February production of The Lion in Winter couldn't have been an easy choice for Pat Nesbit, competing against a Katharine Hepburn incarnation that had won the movie star an Academy Award in 1968. Still, Nesbit took and held the stage with a grace and confidence that made her seem like the first person to ever inhabit the role. She was the very picture of poise, all of her emotions sublimated beneath the smooth politesse that's both royalty's reward and curse. You could call her dignity under duress and her deadpan delivery of devastatingly barbed wit virtuosic, riveting, or any of the superlatives you might ordinarily toss at a great performance. But the most fitting appellation is, simply, queenly.

Best Supporting Actor

Tie: Ken Clement in Rabbit Hole at the Mosaic Theatre and in The Faith Healer at Inside Out Theatre Mosaic Theatre

Ken Clement is a superb actor who can endow big, overwrought roles with surprising subtlety and grace. He does this constantly, but it's rare to see him in a part that flatly demands that subtlety and grace from the get-go. Recently, he's had two. In The Faith Healer, he played Teddy, the titular healer's long-suffering manager after the two had parted ways. Dispensing showbiz wisdom in a bright cockney accent and struggling to hold himself together when suddenly stumbling into the minefield of his own memories, you felt as though you'd known Teddy forever, and it seemed that Clement never existed at all. In last winter's Rabbit Hole, he played a father reeling from the accidental death of his young son. This time, Clement was wild and mercurially unpredictable, swinging from one emotional extreme to another in a way that seemed entirely organic. When his wife — who, of course, was also a grieving mother — accidentally taped over one of the couple's home movies of their lost son, Clement howled in such a way that it was entirely unclear who was doing the howling, the audience or he. Usually, it was both.

Best Supporting Actress

Rebecca Simon in A Bright Room Called Day at Florida Atlantic University

Straddling a fine line between Cyndi Lauper and Johnny Rotten, gleefully decrying the evils of the world like Hannah Arendt screaming on an amphetamine skillet, Rebecca Simon's portrayal of Zillah Katz distilled all the heavy politics of Tony Kushner's anti-fascist dialectic into a punk sneer and a girlish laugh. When she sang a love song to a picture of Adolf Hitler, she communicated the seductions of totalitarianism more completely than Arendt ever did, and the full-bodied lust she put into the number would have made even Kushner nervous. Simon's only a grad student now, but this year, she made most pros look like they were phoning it in. Expect big things.