Illustration by Patrick Faricy

Audio By Carbonatix

Late one Tuesday night, a heavyset man in a worn-out sport coat lumbered out of a sprawling restaurant on Hollywood Beach to his parking spot, the one closest to the building. His basset hounds, Amos and Tillie, tagged along. Even at 78 years old, Joe Sonken was usually the first into the Gold Coast Restaurant in the morning and the last to leave. When not checking on his customers’ place settings or the sauces simmering in the kitchen, he’d hunker down at his corner table with his dogs, reviewing receipts, a cigar clenched between his teeth.

How many times had he pulled out of this spot in the last 33 years?

But on this day in May 1986, his 8-year-old ocean-blue Oldsmobile barreled backward, crashing through the dock and plunging into the Intracoastal. From nearby appeared a Gold Coast regular, a guy who had spent so much time there that a booth could have been named after him. He saw the car in the water and froze. Sonken’s hands remained on the wheel, as if he could drive his way out. Time slowed to a crawl.

“Get me outta here,” Sonken yelled in the last moments before the car sank. “I can’t swim!”

Sonken was Gold Coast, which was famous for stone crabs and called one of the best restaurants in South Florida by the Miami News. It was called other things too: “notorious,” for example, and a hangout for stars such as Frank Sinatra and Cary Grant. A United States Senate subcommittee termed it a national message center for the mob, set up for secret communication between high-powered criminals. The restaurant has cameos in the FBI’s JFK assassination files and the pages of a 1980 Elmore Leonard novel.

When people heard about what had happened to Sonken’s car, many – including some restaurant staff – figured someone had messed with it. Maybe the gearshift had been rigged, the brakes cut, or there was foul play. The next morning, the Miami Herald announced that Sonken, the intimidating icon who had presided over this landmark for decades, had drowned.

His Gold Coast had long been a place of infinite possibility, where an impromptu jazz-concert-as-wake for a blind pianist could be followed by a hostage-taking robbery. Joe Sonken was as much a celebrity as many of the famous people who frequented his restaurant. These days, his name is emblazoned on a building at Nova Southeastern University in Davie and continues to grace charitable grants for causes across the area, including SOS Children’s Village of Florida, Memorial Regional Hospital of Hollywood, and the South Florida Wildlife Center. But today the person behind the name is mostly misunderstood or forgotten, as is the story of his “magic space” (as one restaurateur called the Gold Coast).

Who wanted to put an end to Joe Sonken? Maybe it was the Gold Coast regular who was at the scene in the parking lot. He had run up tabs worth thousands of dollars, and owed thousands more to Sonken in rent for a commercial property. Or perhaps it was one of the scores of mobsters who made his restaurant a second home. Law enforcement – municipal, state and federal – had repeatedly taken shots at bringing down Sonken. Agents were in the midst of a historic undercover operation using the restaurant as a staging ground at the time the car rolled into the drink.

It’s long been assumed Sonken was mafia in a region that for years was bursting with rival crime families. His rise, his polarizing effect on people, even his kindness are both unlikely and illustrative of a South Florida colonized by wise guys and silky-voiced crooners. Stepping back in time through Gold Coast’s doors reveals a reality with more twists than a mob movie.

Joe Sonken (left) was proprietor of the Gold Coast Restaurant and the Cutty Sark Lounge, which were located on A1A in Hollywood.

Joe Sonken photo courtesy of the Hollywood Historical Society/Restaurant photo courtesy of the Myrna and Seth Bramson Collection

There was no way to avoid proximity to mobsters in the hospitality field in 1930s and ’40s Chicago. Born to a father from Russia and a Polish mother, Joe Sonken worked from the time he was 10, leaving school after eighth grade. He entered the meat industry before losing a bundle in the Great Depression and then overseeing a lounge at the Devonshire Hotel in the city’s North Loop. Some alleged Sonken was especially close to Chicago’s underworld, including Al Capone. By one account, Sonken fled to South Florida in his 30s to evade a crackdown on Chicago’s mob-linked establishments.

In Miami, Sonken partnered with two Chicago transplants who’d left the Devonshire under the dark clouds of their reputations: Petey Arnstein, a reputed jewel thief, and Arnstein’s wife, Ollie, identified by police as a brothel madam. The three spent several years running Mother Kelly’s, a stylish Miami Beach nightclub on Dade Boulevard that was advertised as “the rendezvous of the sophisticates.” One night at their club, an armed man assaulted a “dapper Miami gambler,” whipping him in the face with his gun and then opening fire, according to the Miami News. People fled. Sonken, five feet six when he was standing straight, ran right into the gunman’s path to assist his customer.

After selling Mother Kelly’s, Sonken opened Gold Coast Restaurant in late 1953 a few blocks north of the Hollywood Boulevard bridge. He took pride in his Chicago roots and his refined taste for Italian food. The restaurant’s name referenced its double identity – “Gold Coast” was both a term for Florida’s Atlantic cities, including up-and-coming Hollywood, and for the once-swampy stretch of Chicago that through creative redevelopment improbably became elite. Sonken displayed Chicago memorabilia – street signs, pennants, and jerseys – around the restaurant.

Customers arriving by yacht would dock at the back, double-docking on weekends as the restaurant grew in popularity. It was an Old World eatery with small lamps on the linen-covered tables, where diners dressed up for dinner and servers raked away crumbs between courses. Each dish that came out of the kitchen was meant to be a masterpiece, and Sonken showed a knack he’d nurtured at Mother Kelly’s for attracting celebrity clientele. “Don’t come here when you’re in a hurry,” Sonken told the Fort Lauderdale News (forerunner of the Sun-Sentinel) in 1954. “We try to make your dinner the event of the evening.” Musicians played at the piano or strolled around the tables, and one evening Sonken gave permission to a group of enthralled diners to bring his guitarist on their yacht for a cruise. Art Mooney, a well-known bandleader and singer who performed at Gold Coast, recorded a bouncy song inspired by Sonken called “I Never Had a Worry in the World.”

In addition to stars from the sports world and the “other” Hollywood, like boxer Rocky Marciano and The Honeymooners‘ actress Audrey Meadows, who serenaded the restaurant-goers for three hours one night, another crowd made itself comfortable and conspicuous at Sonken’s – gangsters, including the mob’s business mastermind, Meyer Lansky.

Long ago, underworld leaders agreed to make most of Florida a mafia Switzerland, where any mob family could operate freely (the New York-based Gambino family carved out an exception for pornography, which they controlled). They even declared certain areas of South Florida murder-free. Gangsters from the Northeast also enjoyed it for the reasons anyone does – the weather, for one, which hearkened back to the “old country.” Al Capone kept a villa in Miami Beach, where he died after a prison stint for tax evasion. With the spread of air conditioning and jet travel, it became easier to visit or live year-round, spurring a construction boom for which the mob was perfectly positioned. Proximity to Cuba, another paradise ripe for exploitation (and a pre-Castro gold mine for Lansky), added to South Florida’s appeal.

Broward County increasingly tantalized organized crime families. Lansky seized opportunity. He coordinated previously disjointed illegal gambling operations, creating layers of employment, legitimate and otherwise, in a farmland area that had long been depressed.

“[Sheriff Walter] Clark was a pragmatist,” points out Bob Jarvis of Nova Southeastern University Law School, an expert in gambling history. “He realized he didn’t have a big enough police force to take on the mafia,” so he channeled the incursion in a way that pumped up the economy.

Then came a backlash. A rise in investigative journalism on the mafia inspired Sen. Estes Kefauver of Tennessee to hold televised hearings into organized crime, which pressured J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI to step up enforcement. “‘The Life’ was glamorized,” explains Richard Mangan, professor of criminology at Florida Atlantic University. Society columnist Walter Winchell even met with gangsters to learn underworld gossip. A white-hot spotlight landed on the mob and followed it to Florida.

The large rectangular sign rose on stilts against the growing skyline of what was then called “Hollywood-by-the-Sea.” Joe Sonken’s Gold Coast Restaurant, it read. The modest, pallid gold exterior at 606 N. Ocean Dr. (now GG’s Waterfront Bar & Grill) gave no indication of its capacity, which reached 300 after several expansions. The maitre d’ and a share of diners wore tuxedos, but Sonken, son of a tailor, eschewed even a tie. He dressed in a white, open-collared shirt with a dark sport coat and white socks. This led one fashion designer to offer to publicly to dress him. He was short of stature and balding, with a face that was at times pugnacious, and usually inscrutable.

This was Joe Sonken’s fiefdom. He was known simply as “boss.” When a couple complained loudly that the presence of Sonken’s dogs in the restaurant was unsanitary, a flick of his wrist was all it took for the maitre d’ to escort out the troublemakers. Every customer was important, but Sonken didn’t kowtow. He gave the boot to Frank Sinatra and his crew for being disruptive. “Get the hell out of here and take your gang with you,” Sonken said, much to Sinatra’s shock, remembers Thomas Lentini in his memoir, Silk Stocking Bandits. The boss protected his clientele’s peace and privacy.

Sonken turned on a dime from wry to angry. A former busboy recalls clinking two glasses together while clearing a table, when the old man, as staff called the restaurateur, shouted, “Where’s the fucking cocksucker busboy?” Sonken once opened a bag of bagels on a Sunday morning, sniffed, and threw them against the wall. “Those aren’t from Sage!” he said of Sage, Bagel & Deli in Hallandale. If Sonken thought you did something wrong, he would unleash an epic string of profanity. The best way to deal with this was to nod, walk away, and act as if it never happened. Sonken didn’t hold grudges. The joke among waiters was if he liked you, he cursed at you, and if he didn’t curse at you, start looking for a job.

Sonken was a master at publicity. Cary Grant frequented the restaurant when he was in town, at one point giving Sonken a case of Fabergé perfume (Grant was on the company’s board); the restaurateur would hand out gift-wrapped bottles of the perfume to female customers, generating press mentions in the Miami News on top of earlier ones that reported spotting Grant. Local papers also covered how Sonken told diners he’d give them “people bags” instead of “doggie bags” for leftovers. Then there was the fenced-in “cur lot” for diners to leave their dogs outside. When called the “Toots Shor of the South” in 1970 by the Miami News – referencing a famous New York restaurateur – Sonken quipped back that Shor was the “Joe Sonken of the North.”

They orchestrated weapons smuggling and other schemes that were part of a plot to kill Fidel Castro at the Gold Coast.

Almost every night there was a new food critic, chef from another restaurant, politician, or entertainer such as Sammy Davis Jr. at the place. But the presence of the larger-than-life mobsters – the knights errant of modern life – always stood out. In addition to Lansky, Gold Coast regulars included characters with robust rap sheets like Vincent “Jimmy Blue Eyes” Alo, John “Peanuts” Tronolone, and “Fat Hymie” Martin. When a contingent of 40 Chicago gangsters traveled to attend a Miami Dolphins-Chicago Bears game, they packed into Gold Coast.

If South Florida was the mob’s version of Switzerland, Gold Coast was its United Nations, where rival wise guys agreed to get along. The place was dark, quiet, upscale, could be accessed from the water, and had phenomenal marinara sauce. Ben Kramer, a speedboat racer and smuggler, once left $10,000 in cash in a garbage bag in his trunk in the Gold Coast parking lot. “Oh, it was Joe Sonken’s,” he explained later. “I knew the parking lot would be secure.”

Pivotal moments in mob history transpired over homemade ravioli and Gold Coast’s famous Chicken Vesuvio (baked with potatoes and onion). In the early 1960s, mafia powerhouse Santo Trafficante Jr. and mob flunkey David Ferrie (who years later was portrayed with frenetic flair by Joe Pesci in Oliver Stone’s JFK) met other anti-Castro figures at Gold Coast. They orchestrated weapons smuggling and other schemes that were part of a plot to kill Fidel Castro, a CIA operation later investigated for connections to Kennedy’s death, according to FBI files declassified in 1992. (Some of the aluminum ware to make these weapons, the FBI suspected, made pit stops at Gold Coast.) “Tony Pro” Provenzano, of New York’s Genovese crime family, apparently also plotted the as-yet-unsolved Jimmy Hoffa murder at Gold Coast. In a sit-down at Gold Coast with a union leader, capo “Tony Jack” Giacalone, of the mob’s so-called Detroit Partnership, demanded payment for helping make Hoffa disappear.

The heat turned up on Sonken when a 1957 article by columnist Jack Anderson claimed the restaurateur didn’t just serve steaks to the mafia, he was mafia. Less than two years later, another journalist, Kennedy family insider Pierre Salinger, announced to a Senate committee on organized crime that Sonken was “a notorious Chicago figure.” In his seminal book on South Florida’s crime scene, Syndicate in the Sun, journalist Hank Messick referenced Anderson’s allusion to Sonken as a sinister kingpin.

Surveillance was conducted on Gold Coast from the parking lot, from across the street, from the waterway, and by undercover agents with body cameras and recording devices hiding behind Sonken’s big red menus. In one year alone, 2,592 photos of Gold Coast were taken by the FBI. In the mid-1960s, a grand jury on corruption and rackets convened in Broward County with Sonken the marquee name of the investigation. One question asked repeatedly of suspected mobsters was: “Do you know Joe Sonken?”

In 1968, the same year Sonken gave one of his many English bulldogs to a state senator, the Florida Legislature convened an organized crime committee and called in Sonken. “Ever hear of the mafia?” asked Gerald Kogan, the committee’s legal counsel and a future Florida State Supreme Court justice. “Yeah,” said Sonken dryly. Sonken was informed the committee had requisitioned two years of phone records from Gold Coast. “Don’t take two,” said Sonken. “Take ten.” The Fort Lauderdale News ran a photo of Sonken at the hearing, bathed in shadow, appearing angry – though he almost always appeared angry.

When the committee probed a donation from Sonken in the Broward County Sheriff’s race, it learned the restaurant owner had left the candidate an envelope containing two pennies. Once, when Sonken heard a reporter snooping around the restaurant asking about the mafia, the boss waved the phone receiver from behind the bar and announced loudly, “Call for Mr. Capone, telephone call on line two for Mr. Al Capone!” When someone asked what he knew about Meyer Lansky, Sonken would say, “He orders spaghetti.” An FBI report put Sonken’s position this way: Sonken “could not explain why these individuals of the hoodlum element frequent his restaurant, except that he has good food.”

The committee produced nothing concrete against Sonken, but a few years later he found himself dragged into a holding cell at the Broward Sheriff’s Office. One of Sonken’s bartenders, Henry Leddy, had been taking bets on jai-alai and horse races. “Look what them handcuffs did to my wrist,” Sonken complained to Miller Davis, the Fort Lauderdale News crime beat reporter who, like many journalists, was a fan of Gold Coast. The prisoner, clenching an unlit cigar in his teeth, stretched his hands through the cell bars. “I’m 65 years old. I’m a businessman. I don’t bother nobody. But you’d think I killed my mother or something the way the coppers hassled me.” This case fell apart when it became clear Leddy had gone behind Sonken’s back.

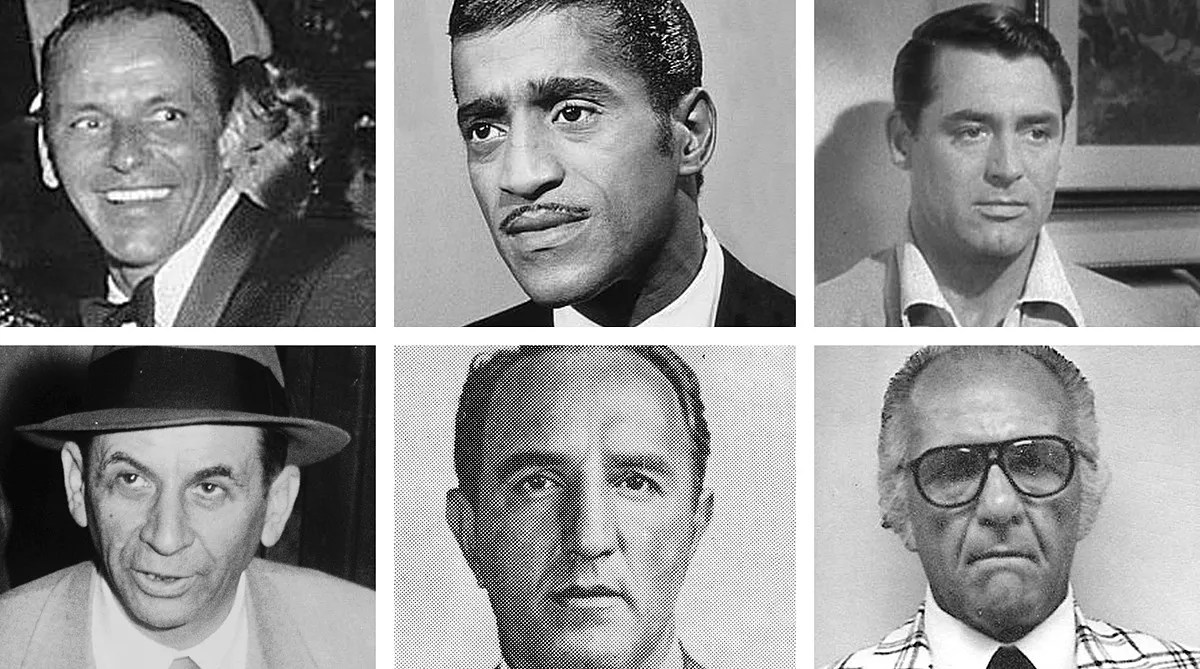

In addition to Hollywood stars such as Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr., and Cary Grant, some of the mob’s heavy-hitters, like Meyer Lansky, Vincent Alo, and Anthony “Tony Jack” Giacalone, would frequent Joe Sonken’s Gold Coast Restaurant.

Photos via Wikimedia Commons

Gold Coast employees could only wish the police were there on Labor Day 1973. Around 4 a.m., as bartenders Ernie Baticki and Joe Galanti exited, two men with black stockings over their heads stuck guns into the bartenders’ backs and said, “Get back inside!” They grabbed $5,080.83 from the register. A man on a walk to get a newspaper saw them and called the police from a pay phone. By the time the robbers were ready to leave, police had surrounded the restaurant they already knew so well. The gunmen handcuffed the two bartenders and the night manager, Gale Pendleton.

“We’re coming out!” one of the robbers yelled as they made their way to Pendleton’s car. “If you try anything, we’ll kill them! We’re coming out, or you’re all dead!”

“You better not hurt the hostages!” called Lt. Neil Robar of the Hollywood Police, ordering his officers to stand down. Once the car with the robbers and hostages began to move, police resumed their positions and opened fire, shooting at the tires. The shots missed their mark, and a high-speed car chase that included local cops and even a helicopter ensued down A1A. After reaching North Miami Beach, the thieves released the hostages and traveled on foot until they were picked up by an accomplice. They tossed the sport coats they’d worn during the robbery into an alley – a miscalculation, it turned out, because the stolen money was in the pocket of one of the coats.

“We’re coming out!” one of the robbers yelled. “If you try anything, we’ll kill them!”

Eventually, Frank Ippolito and Manuel Talavera received sentences for robbery and kidnapping (Talavera, who had two prior robbery convictions, received 120 years in state prison, where he remains). Presumably, either the robbers didn’t know Gold Coast’s reputation or they knew it and that’s why they hoped for a big score. (Another possibility involves internal mob drama, as the FBI believed Ippolito could have been related to a member of a Tampa-based mob syndicate.) Gold Coast had never before been robbed. “I don’t like it,” Sonken told a reporter.

Not long after the Gold Coast robbery, the feds charged Sonken with tax evasion, but a jury acquitted him. In 1978, officers from a state task force burst into Gold Coast amid a busy lunch crowd, alleging Sonken had bought stolen food products. “We’re not fooling around,” a source with the investigation told the Fort Lauderdale News, as officers lugged out 40 cases of mushrooms, 96 cases of tomato juice, and five cases of anchovies.

“I run a good, clean place here,” Sonken complained this time, noting that the dozens of officers who raided Gold Coast’s food “acted like they were looking for John Dillinger.” Stakes were high. The task force, if successful, might have pressured Sonken to turn over information against his big-name customers. But it didn’t work. Sonken claimed entrapment because undercover police had sold him the food and Circuit Court Judge Arthur Franza agreed, throwing out the case and chastising police for an abuse of power that “really shivers the spine of the Constitution.” Sonken went to court to demand his food back.

Gold Coast didn’t miss a meal. But the police weren’t done by a long shot.

Steve Bertucelli, who became director of the Broward County Sheriff’s Office’s Organized Crime Division (OCD) in the 1980s, licked his wounds from the ill-conceived stolen food gambit against Gold Coast, which he had spearheaded as part of the Metro-Dade Police. Gold Coast attracted Bertucelli and his team like moths to flame. “Their members are doing business, even in a social or a relaxed setting,” Bertucelli explained to the Chicago Tribune. “They are here to make money.” The Boston-born Bertucelli later told the Sun-Sentinel of his job that “it was like a chess game.” Bertucelli would have to gird himself to keep taking on Sonken. As longtime Gold Coast employee Rip Ortega remembers, Sonken “wouldn’t let you know how smart he really was.”

Bertucelli, working under Sheriff Nick Navarro (who campaigned on his anti-organized crime bona fides), prepared to launch the daring “Operation Cherokee.” They would send an officer into Gold Coast not just to eavesdrop. He would go in under an assumed identity and become a regular.

Bertucelli had convinced a former colleague, Dave Green, to join his department. Six years earlier, Green had dropped out of undercover work. “It’s a stupid job,” he lamented at the time. “If you want excitement, skydive.” Yet here he was, lured into Bertucelli’s sting. Operation Cherokee would end up taking its toll on Green, his wife, and their three children.

Green called South Florida the “haven for every crud in the United States.” His mission was to collect enough evidence from mafiosi and underworld players, to disrupt the invasive species at the roots. Mingling with people interested in suspiciously low-priced liquor, he zeroed in on Patrick DeCrescito, 59, a bartender at Gold Coast. Green convinced DeCrescito to introduce him to people involved in shady liquor distribution, narcotics, and gambling.

Green would be welcomed, accepted, and get to know Sonken himself. His aim, at least in part, would be unswerving: to finally bring down Joe Sonken and the Gold Coast Restaurant.

Next week: Lawmen deepen their probe into the Gold Coast, and Sonken helps a kid.

© Matthew Pearl, all rights reserved. Pearl, who grew up in South Florida, is a New York Times best-selling author of six novels that have been translated into 30 languages.