Scientists were stumped. It's not uncommon for corals to be affected by diseases or bacteria, but nothing like this had ever been recorded before. The scale and mortality of what scientists now call stony coral tissue loss disease (SCTLD) was unprecedented.

"It's the most devastating coral reef disease we've ever seen," says Dr. Andy Bruckner, a research coordinator for the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary and a coral reef expert.

Once a coral is infected, the disease quickly becomes lethal. Small colonies might die within as little as a week. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) estimates the mortality rate is 66 to 100 percent. Brain corals are particularly susceptible to the disease, including pillar corals — an endangered species.

"It starts out looking a lot like coral bleaching," says Will Fox, owner of Looe Key Reef Resort & Dive Center. "But rather than just killing the chlorophyl part, it kills the entire coral."

Corals are animals that have a symbiotic relationship with the single-cell algae that provide nutrition and color to the reefs. Bleached coral retains live tissue, allowing the reef to eventually recover its colorful mosaic of algae. But SCTLD erodes the tissue of coral reefs, leaving just a skeleton.

Moving with the tides, the disease has spread along hundreds of miles of the Florida Reef Tract. By 2015, it had moved north to Pompano Beach and south through Biscayne National Park. It was spotted in Palm Beach and the upper Florida Keys in 2016 and spread to the middle Keys and Martin County the following year. Half of Florida's 45 reef-building coral species had been affected by 2017, according to a guide issued by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection that year, including five species listed under the Endangered Species Act. The Lower Keys were affected by SCTLD by 2018, and the disease reached Key West in early 2019.

Dry Tortugas National Park remains safe, but likely not for long. The Florida Coral Rescue Project collected corals from the park over Independence Day weekend to rescue them ahead of the disease front. The Rescue Project now cares for more than 1,500 colonies in aquariums or nurseries in South Florida. More than 600 have found new homes at the University of Miami.

SCTLD is now spreading through the Caribbean Sea, according to a monitoring map compiled by the Atlantic and Gulf Rapid Reef Assessment (AGRRA). It has affected 30 percent of corals off the eastern coast of the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico, and it's been spotted in Jamaica, the Dominican Republic, the Virgin Islands, and Saint Martin.

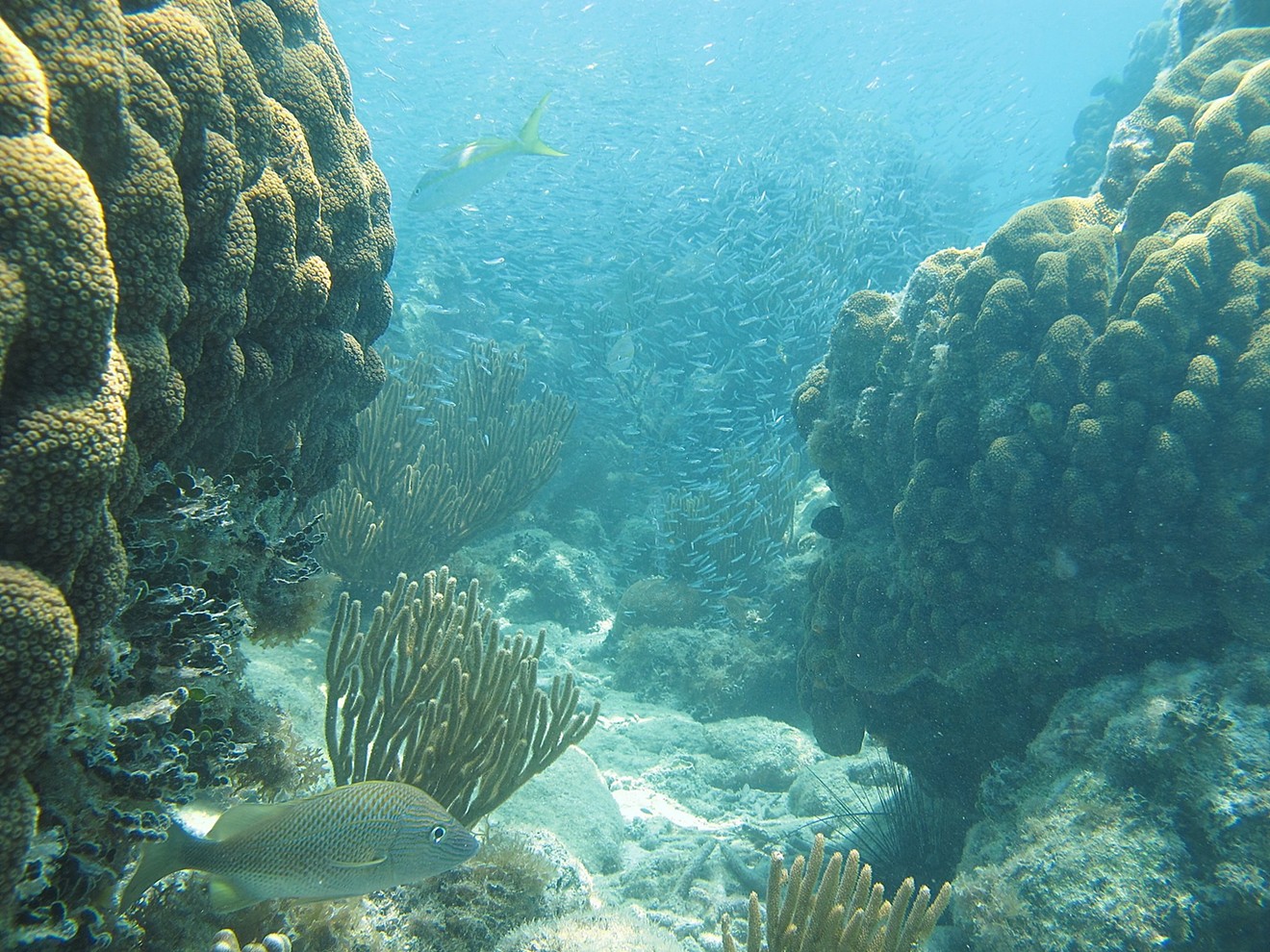

The effect of stony coral tissue loss disease on the Florida reef.

Emma Doyle/Gulf and Caribbean Fisheries Institute

Dr. Brian Lapointe, a research professor and investigator at Florida Atlantic University's Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute, believes the culprit might be a combination of climate change and land-based nutrient runoff. Using 30 years of data from Looe Key Reef in the Lower Keys, Lapointe traces how reactive nitrogen is disrupting the natural chemistry of the coral reefs by outlining three major coral-bleaching events that occurred during periods of heavy rainfall and increased water deliveries from the Everglades.

"Coral reefs have evolved over millions of years in clear, clean, low-nutrient water," Lapointe says. "They've coped with carbon dioxide and high temperatures before. What they have not had to cope with is carbon dioxide, high temperatures, and reactive nitrogen."

Humans have doubled the amount of reactive nitrogen on the planet. The development of fertilizer has fed a growing population, but the topsoil loss from urban and agricultural activities drains into the Everglades and then into the coral oceans. Lapointe explains how the natural nitrogen-to-phosphorus ratio in coral reefs is 16:1, but manmade nitrogen has skewed the Everglades to a ratio of 260:1. When their environment is overloaded with nitrogen, it causes stress and starvation. The last mass coral-bleaching event in Florida occurred between 2014 and 2015 — along with the outbreak of the coral disease. Lapointe thinks the two events are related.

"It's heartbreaking to have so little corals left, but the good news is that here's something we can do about it," he says. "There's hope, and it's actionable: Wee can reduce the human nitrogen footprint both locally and regionally."

Coral reefs are unique, among the most threatened ecosystems in the world, and an integral component of Florida's economy. They occupy only 1 percent of the world's marine environment but provide a home for a wide variety of fish, lobsters, clams, and turtles. They're a major sources of tourism — 4 million visitors traveled to the Keys last year — and support the state's commercial fishing industry. NOAA estimates the Florida Reef Tract generates $8.5 billion annually and provides 70,400 jobs in South Florida. Coral reefs are also the state's first line of defense against hurricanes, protecting coastlines from storm surge.

"We've lost a lot of coral, but there is still hope," Bruckner says. "We've found juveniles and larvae of the coral colonies susceptible to the disease still holding on after the disease has run its course. There's an opportunity to still turn this around."