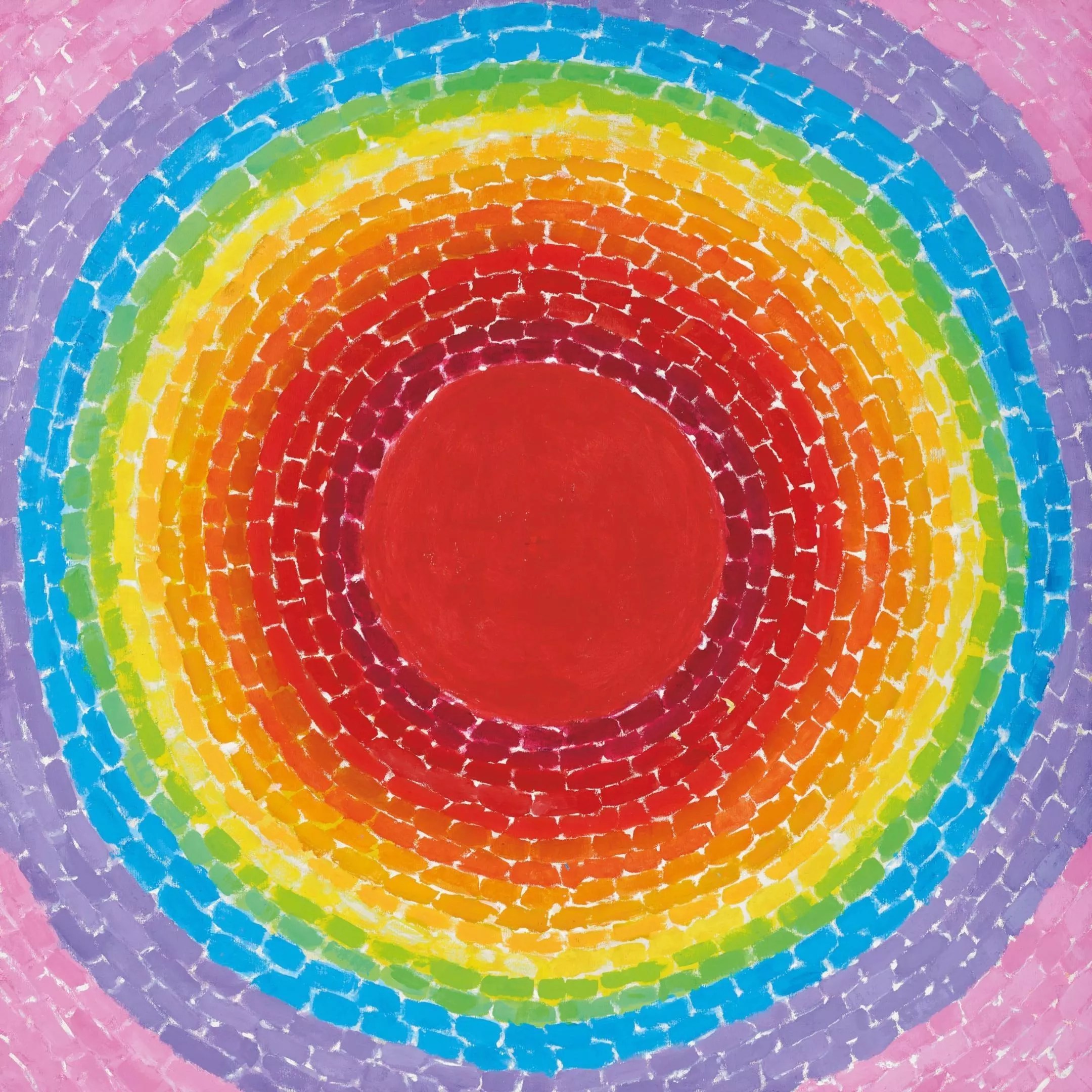

Courtesy Anonymous. © 2023 Estate of Alma Thomas (Courtesy of the Hart Family) / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Audio By Carbonatix

At NSU Art Museum’s ambitious new show on color-field painting, there is one significant omission that lovers of modern art won’t be able to miss. Mark Rothko, whose color-block canvases made him one of the most significant American artists ever, is not here – and that’s the point.

“He made it very clear he was not a color-field artist,” Bonnie Clearwater, director and chief curator of the museum, says. And she knows a thing or two about the abstract expressionist painter – she formerly led the Mark Rothko Foundation.

“The exhibition really is about the generation that comes after because they faced a dilemma,” she says. “They were all committed to abstract painting, and unlike the abstract expressionists who came before them and went through this whole process – going from representational and expressionist art to surrealism and biomorphism, and ultimately to their resolved full-blown abstraction – this generation starts where that ends. Rather than having to go through that exploratory stage, they start with the fact that abstract painting to them means modern art, and to be modern means to be an abstract painter. But how do you create something new now that you know what abstract painting looks like? How do you make something that’s not derivative, that’s new, and right for you?”

“Glory of the World: Color Field Painting (Early 1950s to 1983)” is NSU Art Museum’s attempt to show how abstract painters working in the wake of abstract expressionism – the action painting of Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, the all-encompassing canvases of Rothko and Barnett Newman – tried to find a way forward for the form. The result is a stunning show full of dramatic, awe-inspiring paintings that seek to redefine color-field painting for a new generation. That means centering the contributions of female artists and artists of color.

Helen Frankenthaler, for instance, is credited with catalyzing the movement. With her 1952 painting Mountains and Sea, the New York artist achieved a groundbreaking new style centered on a technique called “soak and stain.” She would take oil paint, add a large amount of turpentine to thin it out, and apply it to a bare, unprimed canvas, letting the color penetrate the fabric. Clement Greenberg, America’s most important art critic at the time, thought it was a massive innovation, carrying on from gestural painters like Pollock.

“He recognized in this painting that Helen Frankenthaler had found a way of taking what Pollock did and opening it up for possibilities,” Clearwater says. “And he brings two artists from Washington, D.C., who were also exploring abstraction, trying to work their way through how you make this original gesture, this original work that departs from the abstract expressionists – he brings them to her studio to see this painting. And it’s the spark for them to pursue their own innovations.”

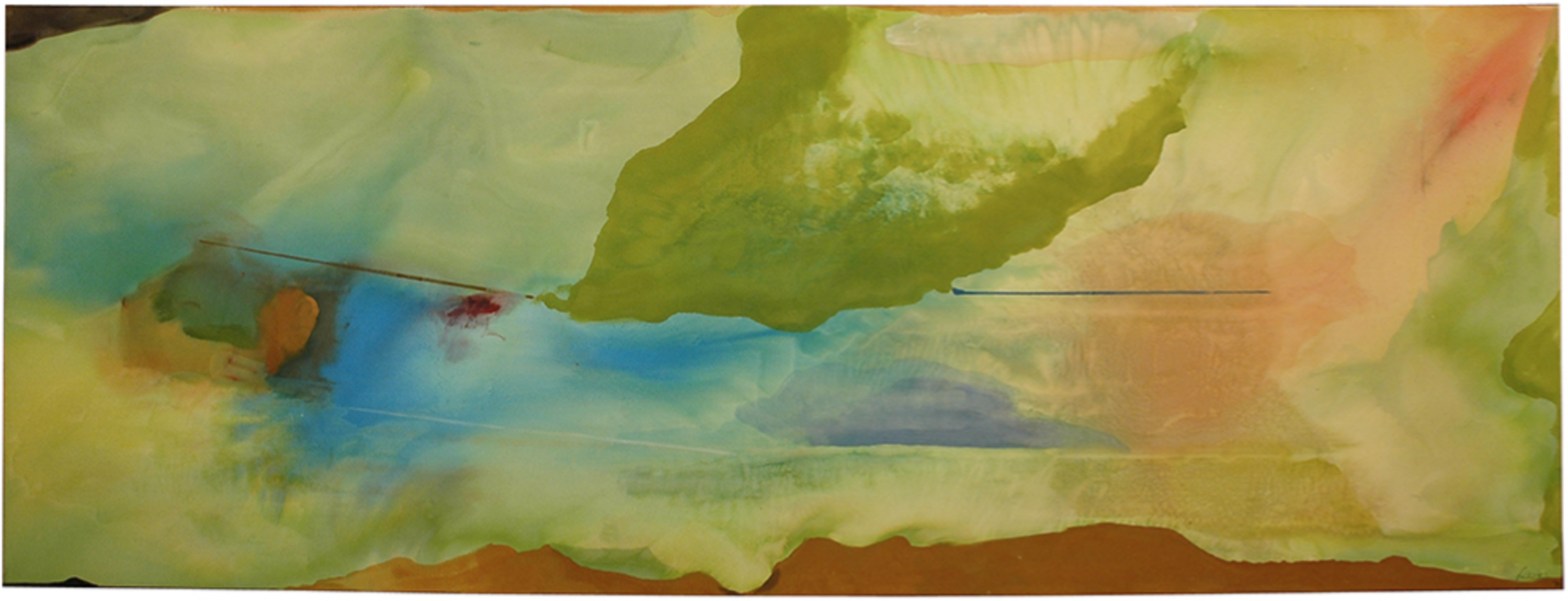

Helen Frankenthaler, Hint from Bassano, 1973

Courtesy Anonymous. © 2023 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Mountains and Sea isn’t in the show – it’s on long-term loan at the National Gallery of Art in D.C. – but the museum smartly places her work throughout “Glory of the World,” letting us see how her innovations inspired succeeding artists. The chain begins with the two D.C. artists Greenberg invited to see the painting, Kenneth Noland and Morris Louis. They took the soak-and-stain technique back to the capital and applied it in their work, founding the Washington Color School in the process. Both incorporated chance into their process: Louis would let paint drip and stream down the canvas, forming unpredictable shapes and layers of color, while Noland played with geometry, creating a series of circular mandalas where the unchanging compositional format allowed the artist to play with varying color combinations. The exhibition places all these paintings in conversation with each other – Louis’ bronze, algae-like Curtain next to Frankenthaler’s burgundy Wine Dark, with Noland’s chevron-shaped Carriage hanging in the next room, visible through the doorway.

The wow factor of these artworks only increases as the show digs further into the possibilities color-field painters explored and the techniques they used. Sam Gilliam’s dazzling Cordial I resembles a nebula, or the brilliant mix of hues found in agate, but look closely, and you can see the places where he folded his canvas while painting it. Ed Clark painted with a push broom, delivering exciting compositions such as Paris Series. Larry Poons threw paint at the canvas in huge globs, resulting in messy, visceral works that shimmer with the iridescence of toxic waste; you can see the results in Regulus, a sludgy, 2.5-dimensional painting that seems to transform as you approach, or Rain Race, which looks like satellite photos of an alien planet. Jules Olitski’s compressed-air spray gun paintings feel dreamy and loose; you can imagine floating in purple clouds looking at something like Comprehensive Dream. And Frank Stella furthered the geometric experiments of Noland, incorporating elements of op art in Waskwalu II (Variations on a Circle) and the square radial Sacramento, which recalls the vibrant set design of Jodorowsky’s The Holy Mountain.

What makes the show feel truly significant, however, is how it centers the contributions of Black color-field artists: Sam Gilliam, Ed Clark, Alma Thomas, Peter Bradley, Al Loving, and Frank Bowling. Many of these artists did not receive recognition until late in life or after their deaths, and according to Clearwater, “Glory of the World” marks the first time they’ve been included in a major museum show on color-field painting alongside their white contemporaries like Stella and Noland.

Clearwater was inspired to set up the show after artist Eric N. Mack curated for the museum “Lineages: Works from the Collection,” which featured paintings by Gilliam, Frankenthaler, and other artists who influenced Mack.

Kenneth Noland, This 1958-1959, 1959

Courtesy Anonymous. © 2023 The Kenneth Noland Foundation / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

“Eric, as a Black artist, like the other artists of his generation, recognized that he had the responsibility to bring attention to those artists that came before him, that he admired, that were breaking new ground, but never got the attention that they should have received,” she says. “He was bringing attention to Sam Gilliam, Frank Bowling, Peter Bradley, this whole generation of Black abstract and color-field artists who are only in the last decade getting recognized for their contributions and innovations.”

The show does have some precedence. Several artists in “Glory of the World” were also featured in “The De Luxe Show,” a 1971 exhibition that took place in a disused theater in Houston’s historically Black Fifth Ward. The show was organized by artist Peter Bradley and collector John de Menil with the explicit goal of bringing world-class abstract art into a community unable to access it. White (Noland, Olitski, Poons) and Black artists (Clark, Gilliam, Al Loving) participated, making it one of the first racially integrated art shows in the U.S.

The show received enthusiastic support from the likes of Clement Greenberg, but even his clout couldn’t get the white art establishment to pay attention to the Black painters. Bradley and his cohort also faced antagonism from the Black Arts Movement, which favored positive, representational imagery and political messaging. But the painter fought back. Abstraction in modern art, he argued, derived from the appropriation of African art by Europeans such as Picasso and Matisse. He wasn’t working in a white art form but reclaiming a Black one.

Alma Thomas felt similarly. Active in the civil rights movement, she embraced abstraction and color as a means of liberation. The deep red at the center of A Brilliant Sunset speaks to the passion she had for color-field painting and its power. She put it best in the wall text, “Through color, I have sought to concentrate on beauty and happiness in my painting rather than man’s inhumanity to man.”

“Glory of the World: Color Field Painting (Early 1950s to 1983).” On view through June 30, 2024, at NSU Art Museum Fort Lauderdale, 1 E. Las Olas Blvd., Fort Lauderdale; 954-525-5500; nsuartmuseum.org. Tickets cost $5 to $16; free for children 12 and under and members. Tuesday through Saturday 11 a.m. to 5 p.m., and Sunday noon to 5 p.m.