Disappointed but not defeated, Schacknow set out to find another location for his museum. He settled on a building in Plantation that had previously housed a CPA firm, and after some remodeling, the Schacknow Museum of Fine Arts returned, phoenixlike, in June of this year. Now SMOFA, as the museum's logo pegs the place, has embarked on its second exhibition, "The Magnificent Eleven," supplemented by "Talking to the Animals," a selection from Schacknow's vast archive of his own works.

Schacknow says his new site has about 8700 square feet of display space, along with three small classrooms and storage space for the nearly 2000 paintings and drawings of his that he and two assistants are in the process of cataloging. And indeed he has commandeered virtually all available wall space for the current shows, which take up not only the many galleries but also the hallways connecting them, as well as the lobby. He estimates that there are more than 200 pieces now on display.

There has always been a strong populist streak to Schacknow, both as artist and as museum benefactor, which is a good thing and a bad thing. He's about as far as you can get from academia and its aesthetic demands, and his enthusiasm for just about any kind of art appears to know no bounds. But that also leaves him open to the charge that he has no standards, or that his standards are so broad and generous as to be meaningless.

Such a charge could be supported by many of the selections included in "The Magnificent Eleven." There's an overabundance of mediocre animal portraits, florals, and still lifes of the sort you might expect to find at one of those traveling outdoor art shows or for sale at discount prices on the side of the road.

Among Sandra Trower's run-of-the-mill oils and acrylics are a leopard, a lion, and zebras, while Edwin Adler's parade of a cat, chickens, a rooster, and a few still lifes includes a cheesy portrait of Elizabeth Taylor. Adler also provides Joys of the Beach, an oil portrait of a bouncy female nude who might have been inspired by Bo Derek. He almost redeems himself with Gate Under the Sun, a small painting that's labeled "oil" but looks more like a delicate watercolor of a tranquil garden area. (It's echoed in a later gallery by Palm Spring, another appealingly understated take on a quiet courtyard setting.)

The works of one artist in the large main gallery to the right off the front lobby breathe new life into familiar material. In such generically titled paintings as Croton, Seagrape, and Palm, Virginia A. Thompson, working sometimes in oil but mostly in watercolor, captures the lush tropical foliage of South Florida and the sunny light that illuminates it with precision and an intuitive feel for color, especially fine gradations of gold and green. With Morning Light, a simple image of an empty wooden chair casting a lattice of shadows on a bedroom wall, she again displays a knack for light, this time using a muted palette of brown tones.

Also in the main gallery are a mixed bag of sculptures by Plantation-based Anne Herbst. A Grecian head and a bust of George Washington are straightforwardly realistic, while the artist overdoses on whimsy with Strawberry Shortcake, a wood-andmixed-media piece that plants a long, tapered candle on a blocky black wedge of cake. The joke misfires here, although Herbst's sense of humor clicks for her stylized bust of George Bernard Shaw, a caricature as deftly on the mark as a Hirschfeld drawing.

There are other standouts here and there: the thickly stippled pigment that pushes Susan Tauber's Reflections of Shark Valley to the edge of abstraction, the dry wit of Kenneth Karnath's small watercolor Outsmarted Again and its juxtaposition of a fish with the rod and reel it has escaped. But the sheer volume of the show gets to be overwhelming -- there are so many pieces, and so little breathing room for them, that they begin to seem interchangeable.

Four of the eight smaller galleries are designated showcases for Schacknow's work. I can't muster much enthusiasm for the countless images of dogs and birds, especially the oils in "Max's Gallery 2" (which also houses three large, alarming alabaster busts of clowns by Stan Switkes). More-exotic fauna, including the title animal in Rhino and the commanding elk in First Snow, are stronger examples of Schacknow's unorthodox technique of drawing directly on canvas in pencil.

"Max's Gallery 3" features more animal portraits in pencil, along with a prominently displayed portrait of John Ritter, of all people. But the real treasure here is a fine pencil rendering of filmmaker John Huston (misidentified on the ID panel as John Houston). Schacknow's pencil-on-canvas technique proves perfect for capturing the subtleties of the great man's craggy face, its wrinkled cheeks and furrowed brow combining to convey a faintly quizzical attitude.

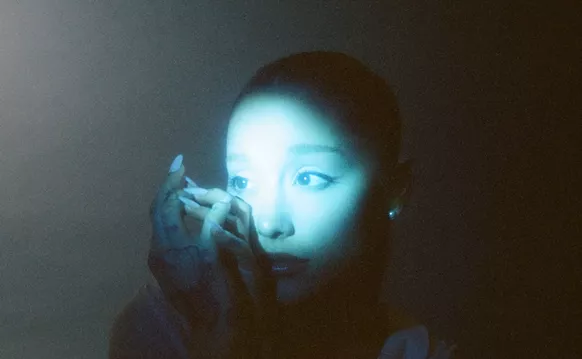

Schacknow's one real find here is the photographer Elena Comens, whose black-and-white prints take up "Gallery 1" and "Gallery 2." A brief biographical note informs us that Comens has studied with Mary Ellen Mark, whose influence is obvious in Comens' stripped-down, documentary approach to her subjects. The two dozen or so photographs in the first gallery are images of day-to-day life in Guatemala -- market scenes, candid portraits, scenes of domestic activity -- the strength of which is their simplicity.

The 20 Comens photos in the next gallery are from Russia, and they're even more powerful in their stark directness. A solitary, melancholy-looking man strides toward us on a cobblestone street in Beneath the Bridge, St. Petersburg. Five stern-faced guards go about their duties in Lenin's Tomb, Moscow. Rows of lights punctuate a dark depot in the grainy Moscow Metro I.

Taken together, such images provide an atmospheric commentary on an unstable society in flux. They're political by implication, as in Free Enterprise, which gives us four men selling their wares on a street, with banners depicting Lenin waving in the background.

Comens' work deserves that main gallery all to itself. Then again, Schacknow's impulse to wow us with quantity suggests that he may have no idea how much better she is than most of the other artists in this show. He's too concerned with the big picture to worry much about the small details.

The big picture, of course, is the museum itself, and Schacknow's determination to establish a venue for art in western Broward is certainly commendable. But often it's the small details that can lift an ordinary exhibition to the extraordinary. If Schacknow can afford to launch his own museum, for example, surely he should be able to spring for a professionally printed brochure for a show of which he's so proud, instead of the typo-riddled, photocopied piece that accompanies "The Magnificent Eleven."

And how credible is a similarly photocopied brochure soliciting membership in the museum when it can't even get the names of some of the best-known artists in history right? Of the six membership categories named for those artists, only two -- Picasso and Renoir -- are spelled correctly. Would you want to shell out $75 for a "Reubens" membership (does it include a sandwich?), $500 for a "Rembrant," or $1000 for a "MichaelAngelo"? The Schacknow Museum of Fine Arts is a fine idea, but unless Max Schacknow starts paying attention to the details or hires someone to do it for him, he'll never have a first-class museum.