Illustration by Pete Ryan

Audio By Carbonatix

With no remaining options, Lazaro Rodriguez could only beg Miami-Dade County Judge Andrew Hague for mercy. But his pleas were in vain. Hague was yelling at him now – in English, a language Rodriguez barely understood. With no one in the room to translate Hague’s words into Spanish, Rodriguez – a tall, burly man with a head of curly hair and, at the time, a long powder-white beard – appealed for help.

“Please,” Rodriguez begged Hague, according to a transcript of the hearing that day. “Please.”

But Hague wasn’t having it. Frustrated after a contentious morning trial where absolutely nothing had gone smoothly, the judge raised his voice, declared Rodriguez guilty, and demanded he write a letter apologizing to the cops who’d arrested him December 17, 2015, for, allegedly, refusing to obey their commands during a simple traffic stop. Humiliated, Rodriguez began to choke up.

“Mr. Rodriguez, this is how this whole thing happened,” the judge bellowed. “You have a temper, and you sit there and did not want to listen to what the officers wanted to say. The letter of apology is what’s getting you tearful?”

“No,” Rodriguez replied. “You don’t know the truth. That’s what hurts.”

For months, Rodriguez had tried to tell his side of the story. He’d been arrested for allegedly speeding, mouthing off to the cops who’d pulled him over, and then getting out of his car to scream at officers against their orders. He’d been charged with threatening a public servant and resisting a pair of officers without violence- one felony and two misdemeanors. But while he admits to verbally sparring with the officers, he maintains he grew angry only because the cops insulted him. In fact, he says, when he was pulled over with his wife in the passenger seat, one of the cops remarked he wanted to have sex with her. From that moment on, Rodriguez was determined to fight his charges in court and prove he wasn’t the one acting out of line that day.

He nearly succeeded. He had requested a public defender, who spent weeks digging into his case, but when it came time for trial, a peculiar thing happened: Prosecutors said they were dropping Rodriguez’s felony charge and one of his misdemeanors. They were no longer seeking to jail him for the other misdemeanor count. And thanks to a quirk in Florida law, Judge Hague said Rodriguez was no longer entitled to a public defender. According to a little-known state statute, criminal defendants who aren’t facing jail time have no right to a state-appointed lawyer in court. With no attorney to fight on his behalf, Rodriguez was convicted and forced to pay $358 in court fees. The criminal conviction went on his permanent record.

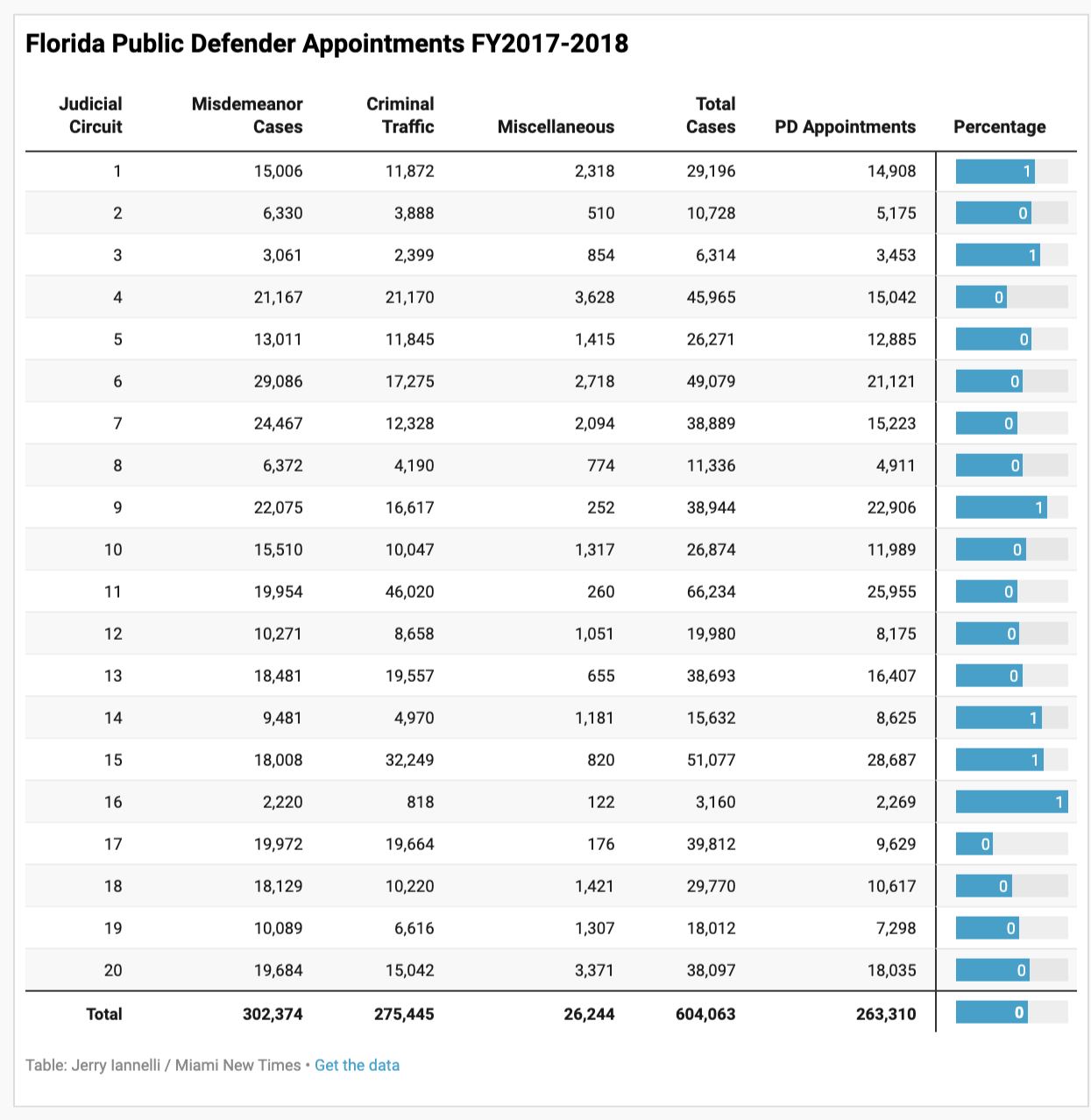

The right to a lawyer is a bedrock principle of the American justice system. But for decades, thousands of defendants have passed through Florida’s misdemeanor court system without any legal representation. For the past three months, New Times analyzed multiple state databases to provide the most accurate estimate to date of that occurrence in all 20 court circuits in Florida – and the results were bleak. Each year, public defender’s offices report their total caseloads to the Florida Public Defender Association. New Times cross-referenced that data with state records to show the percentage of cases in each court circuit where public defenders were appointed in misdemeanor, criminal traffic, and other low-level cases in the 2017-18 fiscal year, the last year for which full data is available.

Miami New Times

Many of Florida’s smaller counties fared well. In Monroe County’s 16th Judicial Circuit, for example, public defenders in the Keys worked on more than 71 percent of applicable misdemeanor and criminal traffic cases. But in the state’s most populous counties, the numbers dropped precipitously. In Miami-Dade, public defenders were appointed in only 39 percent of 66,234 cases. In the Fourth Circuit, which covers Jacksonville, they were only appointed to 32 percent of misdemeanor cases. And in Broward, by far the worst-scoring county in the state, only 24 percent of misdemeanor and criminal traffic cases proceeded with a public defender in the courtroom. Of all misdemeanor cases statewide, only 45 percent occurred with a public defender present.

The state does not keep records on the number of court cases in which defendants hire private attorneys. But in 2011, the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers conducted a study of the Florida misdemeanor court system and determined that only 13 percent of misdemeanor cases occur with a private attorney present. So it stands to reason that thousands upon thousands of people are passing through Florida’s courts and pleading to criminal charges without any expert legal advice.

“These people aren’t going out and hiring private attorneys,” Gordon Weekes, the associate chief public defender in Broward County, tells New Times. “We’re just missing people.”

It costs $50 to apply for a public defender, a fee many defendants cannot afford.

Studies show that defendants who appear in court without a lawyer are significantly likelier to accept plea deals from prosecutors, spend extra time in prison, and pay higher court costs. Though most misdemeanor cases don’t go to trial, the defendants who do make it there are forced to do legal research, call witnesses, conduct cross-examinations, and produce evidence themselves.

After New Times analyzed data for every court circuit in Florida, studied hundreds of court cases, examined multiple academic studies, and spoke with dozens of legal sources, one thing is abundantly clear: Two provisions in state law are creating massive roadblocks that discourage low-income defendants from obtaining what most Americans assume to be basic: constitutionally protected legal help.

For one, it costs $50 to apply for a public defender in Florida, a fee many defendants cannot afford. They can also be charged for additional defense fees after their cases end. Though fees for public defenders are common in some states – especially those in the South with traditionally conservative legislators – Florida is the only state in the nation where a judge cannot waive the $50 application fee for a state-appointed lawyer.

Even if someone chooses to pay for a public defender, in many instances a judge can take away the person’s state-appointed lawyer if the charges don’t require jail time. To strip people of their attorneys, prosecutors first file a notice that the state is not seeking jail time in a criminal case. Judges must then determine whether the decision won’t “substantially prejudice” someone forced to defend themselves without an attorney.

Misdemeanor courts handle the bulk of most criminal cases in any state – and critics say these two laws are creating a factory-like system that encourages prosecutors and judges to churn through cases whether defendants have lawyers or not.

Few outside groups have attempted to solve the problem. Rodriguez, along with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), sued the state in 2017, but his suit was ultimately thrown out.

“What struck us with how it works in Florida, the prosecutor has to move for an order of ‘no incarceration’ – and then judges are just doing this whenever the DA [district attorney] asks for it,” Rodriguez’s ACLU lawyer, Brandon Buskey, tells New Times. “They’re not evaluating whether there would be quote-unquote ‘substantial prejudice’ to the defendant in cases like this.”

If prosecutors know they have a weak case, he says, they kick public defenders out of the courtroom so they won’t be able to pick the evidence apart. Buskey says judges often assume that because the defendant won’t wind up in jail, what happens in the courtroom won’t be all that bad.

“But often,” he says, “the civil consequences – losing your job, deportation – can actually be worse than jail time.”

Statistics compiled by New Times show less than 40 percent of misdemeanor court cases occurred with a public defender present in the 2017-18 fiscal year.

Photo by Aaron Davidson/Getty Images

The U.S. Supreme Court gave all Americans the right to a lawyer only in 1961 – and it happened thanks to a man from the Florida Panhandle.

Clarence Gideon left the Bay Harbor Pool Room in Panama City June 3, 1961, with a wine bottle in his hand and a wad of cash in his pocket. Gideon – a skinny man with a sharp jaw, long nose, white hair, and wide ears stretching out like bat wings – had run away from home as a teen and possessed only an eighth-grade education. He shot pool to unwind. Upon leaving the bar that day, he had no idea he’d wind up sparking one of the most significant legal cases in American history.

As it turns out, someone robbed the Bay Harbor Pool Room early that June morning. Police reported that a burglar had broken through a door, smashed a cigarette machine open, destroyed the record player, and swiped cash from the register. A witness said he’d seen Gideon carrying wine and cash while walking home from the pool hall at 5:30 that morning. Based on that single witness statement, Panama City cops charged Gideon with breaking and entering with intent to commit petty larceny.

At the time, federal law did not force states to appoint public defenders for people who couldn’t hire their own attorneys. Florida law said the only people guaranteed public defenders were those facing the death penalty. Gideon, a poor man who worked various manual-labor jobs and who already had a criminal record, had no cash to defend himself.

“Mr. Gideon, I am sorry, but I cannot appoint counsel to represent you in this case,” a Florida judge told him, according to court transcripts. “Under the laws of the State of Florida, the only time the court can appoint counsel to represent a defendant is when that person is charged with a capital offense. I am sorry, but I will have to deny your request to appoint counsel to defend you in this case.”

“The United States Supreme Court says I am entitled to be represented by counsel,” Gideon responded, to no avail.

Much like Lazaro Rodriguez did decades later, Gideon called his own witnesses, cross-examined state experts himself, and still lost his trial. He was convicted and imprisoned. But while sitting behind bars, Gideon filed an appeal with a novel argument: If the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution guaranteed people the right to counsel in federal cases, shouldn’t the same be true in state courts?

Gideon wound up appealing his case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which, in one of the most consequential court decisions in American history, unanimously agreed with him. On March 18, 1963, Justice Hugo Black wrote in a majority opinion: “From the very beginning, our state and national constitutions and laws have laid great emphasis on procedural and substantive safeguards designed to assure fair trials before impartial tribunals in which every defendant stands equal before the law. This noble ideal cannot be realized if the poor man charged with crime has to face his accusers without a lawyer to assist him.”

But in the five decades since Gideon v. Wainwright, Black’s words have not been fully realized. The Supreme Court has repeatedly affirmed that poor defendants in virtually all criminal cases have a constitutional right to a legal defense. Yet many states still have laws that allow prosecutors and judges to boot public defenders from courtrooms for various reasons. And the majority of states charge defendants – even those who are homeless or indigent – for access to a court-appointed lawyer. In a 2014 investigative series, NPR found 43 states still allow courts to charge defendants public defense fees despite the fact that public defender’s offices were created to protect people who cannot pay for a legal defense.

There appear to be relatively few national, top-down studies about the number of Americans representing themselves pro se in court proceedings. But a handful of criminologists have devoted their careers to studying the issue. The problem appears to be most acute in state misdemeanor courts, where charges for anything from simple battery to driving with a suspended license at least might seem less severe than those in felony courtrooms, where prosecutors are often less willing to cut plea deals and where charges can lead to years in prison or, in the most extreme cases, death row.

Nearly ten years ago, University of Tampa criminal justice professor Alisa Smith became so curious about pro se defendants in Florida courts that she began sending her students to observe legal proceedings in nearby Hillsborough County courtrooms. Her students brought back horror stories, including tales of numerous defendants not understanding they had agreed to put criminal charges on their records permanently. Many defendants, she says, thought they were simply paying fines to make charges go away. And overworked judges were often failing to inform defendants that pleading to criminal charges could permanently affect their ability to get hired or obtain legal immigration status.

Eventually, the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers got wind of Smith’s research and asked to partner on a report, which she ultimately released in 2011 as “Three-Minute Justice: Haste and Waste in Florida’s Misdemeanor Courts.” In that report, she urged the state to, at a minimum, abolish the $50 public defender application fee, which she says discourages an untold number of indigent defendants from applying for basic legal representation. But in the years since Smith released her report, the Florida Legislature has done virtually nothing to remedy what seem like eminently fixable problems.

“This is a rampant problem in misdemeanor courts,” Smith tells New Times. “Without counsel, people aren’t being adequately informed that these aren’t just minor cases. There are long-term consequences to even a misdemeanor case with no jail time. Say you plead to a minor marijuana charge. I’ve asked people, ‘Do you have any idea if you’re gonna lose your job?’ And I’ve had people tell me: ‘I didn’t even think of that.'”

A local judge stripped Lazaro Rodriguez of his public defender and forced Rodriguez to represent himself at his trial in 2016.

Photo by Karli Evans

Lazaro Rodriguez says he grew up having to fight. He immigrated to Miami from Cuba in 1980, and once he became old enough to work, he began running a cash register at a convenience store in Little Havana that mostly sold liquor. In the ’90s, he says, it was a high-crime area. Drug addicts came into the store. Other people tried to shoplift. He had to build up a tough exterior to survive his daily grind.

So when he says Miami Police Officer Nestor Amores and a trainee cop stopped Rodriguez and insulted him in 2015, he felt he had no option but to talk back.

At the time, Rodriguez had a long white beard, which he told the cop was because he was going to dress as Santa for his family that December.

“The cop looked at me and said if I wanted to be Santa Claus, he was going to fuck my wife and see if I still felt like Santa Claus,” Rodriguez tells New Times in a mix of English and Spanish. “How was I supposed to respond?”

According to an arrest affidavit from that day, police say Rodriguez began hurling insults at the cops from inside his car. Rodriguez says he was ordered out of his car, but arrest documents allege he got out on his own. Rodriguez says as he stood to exit his car, his shorts fell to the ground. According to him, one of the cops then kicked his shorts away and forced him to stand in his boxers in a public parking lot. Eventually, the cop handcuffed him. As the cuffs clicked on, Rodriguez’s eyeglasses fell off his head and a cop stomped on them and shattered them, he says.

In arrest documents, though, Officer Amores alleges Rodriguez refused to leave after being issued a speeding ticket and called the cops “pieces of shit” for pulling him over. Amores also writes that Rodriguez was ordered to leave but refused; the officer adds that Rodriguez was arrested only after he declined to place his hands on the hood of his car. The cops admit to dragging Rodriguez across the ground, with one officer grabbing each arm, but they claim it was because Rodriguez refused their orders to move.

Afterward, Rodriguez says, he was subjected to a “nickel ride” or “rough ride,” a potentially fatal practice by which cops place a handcuffed suspect in the back of a cruiser and alternate between accelerating and braking to force the suspect to slam into the divider between the front and back seats. Rodriguez says his face smacked the plastic partition.

City records show Rodriguez later filed complaints against Amores with the Miami Police Department’s internal affairs unit and the city’s Civilian Investigative Panel (CIP). Internal affairs labeled the complaints “inconclusive,” and the CIP, after failing to reach Rodriguez, closed the case. (In court under oath, Rodriguez also attempted, in broken English, to accuse Amores of misconduct by stating the cops “took off again, speeding up, and braked again,”but Judge Hague threw the statements out and told Rodriguez he was talking out of turn.)

Once Rodriguez made it to the Turner Guilford Knight Correctional Center, Miami-Dade County’s main pretrial jail, he applied for a public defender, bonded out, and waited weeks for his trial to begin. But he later learned his appointed attorney had been taken away because the state was no longer seeking to imprison him. He debated simply taking a plea, but he says he was so angered by the way the officers treated him that day that he steeled himself to go to trial – no matter what.

Biscayne Park officers habitually filed cases at a satellite courthouse where public defenders often aren’t present.

Photo courtesy of Village of Biscayne Park

Raimundo Atesiano is the former chief of the 15-person Biscayne Park Police Department, which serves a tiny Miami-Dade town of only 3,000 people. Atesiano, a man with a shaved head and scraggly mustache, is now serving a three-year prison sentence after the FBI caught him framing three young black men for burglaries they didn’t commit.

But the travesty in Biscayne Park could have been avoided. Carlos Martinez, Miami-Dade’s chief public defender, says Florida simply needed more public defenders in its courtrooms.

“If we’re not overseeing all those cases, we can’t notice what might be bad patterns in, say, certain police departments,” Martinez says. “We can’t see if, say, an entire traffic stop started because of, frankly, bullshit reasons. And we then can’t follow up and ask if this was just a one-time thing or if whole departments are being trained to act this way.”

Some cops, he says, seem to know how to file cases to avoid getting public defenders involved. Since Atesiano and three of his cops pleaded guilty to federal charges in September 2018, Martinez has been looking at the department’s entire caseload from that era, and he says he’s found some staggering facts. For one, state ticketing data shows the tiny department was filing thousands upon thousands of traffic tickets per year – so many that Martinez is skeptical many of the citations were issued legally. In 2011 alone, Atesiano himself wrote 2,236 tickets, according to city documents. Some of those cases wound up leading to criminal traffic charges – and, Martinez says, officers habitually filed those cases at the North Dade Justice Center, a satellite courthouse on Biscayne Boulevard in North Miami Beach where Martinez’s public defenders often aren’t present.

In felony cases, prosecutors in the Miami-Dade State Attorney’s Office review police arrest affidavits and re-interview witnesses to ensure that case evidence is sound and that officers followed the law when making arrests. But prosecutors conduct no such review in misdemeanor cases, except when they involve domestic violence. When he was recently invited to speak to State Attorney Katherine Fernandez Rundle’s latest class of prosecutorial hires, Martinez begged them to stop issuing orders of “no incarceration” and trying cases without defense lawyers present, he says.

For years, Martinez has been pushing local and state officials to change the key provisions in Florida law that could alleviate the issue. In Massachusetts, for example, cases without the threat of jail time are automatically converted to civil cases, something he’d like to see adopted in the Sunshine State.

“When I talked to the prosecutors, I was hoping they’d be a check on the system. And they are legally required to be a check on the system,” he says.

But he says misdemeanor prosecutors tend to be the youngest and least experienced lawyers in most county offices. “It is very difficult to expect a brand-new lawyer to be standing in court and start dismissing stuff when they want to get promoted. There’s nothing that tells them, ‘Hey, if you dismiss cases, you’re not going to get promoted,’ but I’m pretty sure that people feel the pressure. It’s too much to ask recently hired prosecutors to be a shield against wrongdoing.”

“Misdemeanor convictions are hopelessly screwing over immigrants all day every day.”

For decades, Martinez has repeatedly watched people plead to charges without understanding the case would go on their permanent criminal records, he says. Yet consequences for even low-level traffic charges can be severe. For starters, in most workplaces, employees can easily be fired for pleading to any misdemeanor. And in Florida, those who fail to pay their court fees are stripped of their driver’s license as punishment. According to the nonprofit Fines and Fees Justice Center, more than 71 percent of license suspensions statewide occur because drivers failed to pay court fines. Losing a license then has consequences of its own: People who already cannot afford lawyers suddenly cannot drive to work, shuttle kids to school, shop for food, or take care of loved ones. They need to rely on others for transportation, stay off the road, or risk getting rearrested for driving illegally.

Moreover, immigration lawyers and immigrant-rights groups warn that even if someone pleads to a low-level charge that leads to only a court fee, federal authorities could still use the conviction to begin deportation proceedings on undocumented defendants.

Asked how often he deals with immigrants facing deportation after pleading to misdemeanor charges, Miami immigration attorney Joe Lackey just starts laughing.

“All day,” he says, “more often than you respirate. Misdemeanor convictions are hopelessly screwing over immigrants all day, every day. If the state is not seeking jail, you don’t get a defender. It’s a tactic. One of the first things prosecutors do is they realize they don’t want the public defender using their brain, so the state certifies non-jail. Then they’ll ask for the PD [public defender] to be discharged – boom – motion granted. Then the state is happy. The defender is happy too, because that’s one less case they have to worry about. The immigrant thinks he or she is happy because they don’t have to go to jail.”

But Lackey says innumerable immigrants plead to charges without understanding that even a misdemeanor case could still lead to deportation.

“People don’t realize there’s a lot worse than jail out there,” he says, “like being sent back to a country you’ve never really even lived in.”

Not long ago, Lackey says, he was standing in a courtroom at the Richard E. Gerstein Justice Building, the drab, fluorescent-lit box that serves as Miami-Dade’s main criminal courthouse. He was waiting for his client to appear when a man born in Haiti stood before the judge to face a misdemeanor charge for improperly using a gun. With no lawyer guiding him, the man was about to plead guilty, serve no jail time, and simply pay a fine to the court – seemingly without knowing that if he took the deal, he’d likely be sent back to Haiti.

“As I heard him start to take the plea, my eyes tripled in size,” Lackey says. “The judge looked at me because she knew I’m an immigration lawyer. So in the middle of the plea colloquy, I walked over, grabbed the guy by the shirt, and physically pulled him away and out the door. The judge didn’t even stop me. She must have said something like, ‘We’ll be in recess.'”

Lackey says the man began yelling at him in the hallway.

“Who the fuck are you? Get your hands off me!” Lackey says the guy yelled at him. (He gave the man his business card but never got his name.)

“Shut up!” Lackey yelled back. “Listen to me! Do you want to go back to Haiti? You’re not pleading to this.”

Lackey says prosecutors who followed the two into the hallway began complaining he was giving the guy free legal advice.

“I was so mad I was having trouble forming complete sentences,” Lackey says. “I was just like, ‘Haiti! No! Plea! Bad!'”

Hialeah police arrested Darryl Burke Jr. for loitering after they couldn’t prove any other wrongdoing.

Hialeah Police Officer Felix Elias couldn’t prove Darryl Burke Jr. was a burglar. The officer had heard there were some people robbing homes in the area. According to arrest paperwork from September 11, 2017, Elias stopped Burke and a group of his friends, all black men in their early 20s, and asked what they were doing driving around so soon after Hurricane Irma had passed through town.

The men said they were heading home. After searching them, the cop writes in his report, he found unspecified “tools” and asked if they were using the items to break into homes. The men said no. Elias says he had no evidence to prove any of the men had broken into any homes that day. So he arrested Burke for loitering.

“Due to conflicting stories and the [defendant’s] failure to dispel my alarm, the def/co-def were arrested for the safety and protection of persons and property in the immediate vicinity,” Elias writes in arrest paperwork.

Court records show Burke made his way through the Miami-Dade misdemeanor court system without a lawyer. He pleaded guilty to loitering charges that year.

Without a lawyer to argue that his charges might have been bogus, Burke served 100 community service hours. He was not able to pay his court fees on time, and state records show his driver’s license was briefly suspended and his fees were sent to a collection agency. (New Times was unable to reach Burke for comment.)

Burke’s case highlights the nature of virtually all cases of “loitering and prowling,” a subjective charge for which a cop essentially decides someone is standing where they don’t belong.

“Loitering is a charge where, 80 or 90 percent of the time, the charges are bogus,” Martinez says. “If you have a defender in there, almost all the time, we get the charges thrown out.”

“Loitering is a charge where, 80 or 90 percent of the time, the charges are bogus.”

New Times analyzed 200 of the 370 loitering cases from the 2017-18 fiscal year – the results show those who passed through the court system without a lawyer were slightly likelier to wind up convicted for simple loitering. But public defenders were far likelier to win their clients sentences of “adjudication withheld,” meaning defendants would agree to pay court fines but not have any criminal charges placed on their permanent records. Simply put, it’s a maneuver that most people without legal training don’t know is available.

On August 31, 2017, Dehjahn Swain suffered a fate similar to Burke’s. According to arrest paperwork, a Miami police officer noticed Swain and another man, both black, simply standing on a sidewalk on Florida Avenue in the historically black area of Coconut Grove.

“This particular area is a well-known high-crime area with a history of shootings, robberies, occupied burglaries, narcotics sales, and narcotics use,” the officer writes in a report. He says that after watching the men “standing in front of” a house for 30 minutes, he questioned what Swain was doing. Swain initially claimed he lived there, but a records check showed the address belonged to neither man. The officer writes that he observed “one large loose crack rock” sitting on a tree stump nearby but was unable to prove whether either man had possessed it. So, instead, he arrested Swain for simply loitering.

Neither of the men could “dispel my alarm as to the safety of persons or property in the area,” the cop wrote. “Both defendants arrested.”

New Times‘ attempts to reach Swain were unsuccessful. Neither Swain nor Burke responded to letters delivered to addresses listed as theirs in court records.

But like Burke, Swain passed through the system without a lawyer. He declined to pay for a public defender. And a local judge found him guilty.

Carlos Martinez, Miami-Dade’s chief public defender, says Florida needs more public defenders in its courtrooms.

Without a public defender to help him, Lazaro Rodriguez never learned of the time in 2013 when the cop who arrested him, Nestor Amores, used his Taser on a driver, who was then shot in the neck by Amores’ partner.

With some digging, Rodriguez’s public defender could have easily referenced that case in court to bolster Rodriguez’s claims of misconduct. In the 2013 case, Amores was working an off-duty security detail at Marlins Park when he stopped 32-year-old Emmanuel Reyes for allegedly speeding. The officers ran Reyes’ info and discovered he’d been driving with a suspended license and had a separate bench warrant out for his arrest. Amores and his partner, Zulema Dominguez, say that when they walked back to Reyes’ car, he placed his hands on his steering wheel and looked like he was about to flee. So Amores yanked Reyes out of the car and fired his Taser.

The cops claim the stun gun had no effect. Instead, they say, Reyes reached into his car and grabbed a “metal object.” They claim he pointed the object at them. Dominguez claims she thought the object was a gun. So she shot Reyes straight through the neck and in the stomach. Reyes collapsed onto the ground as blood spurted from a severed artery.

“You just killed me!” Reyes allegedly yelled as he clutched the wound. The “object” was a metal box full of drugs – not a firearm.

Miraculously, Reyes survived the incident. In a lawsuit filed against the department, he said he slipped into a coma for two months and now lives with permanent disabilities. Reyes said he never pointed the box at anyone. (He and the city later settled the case out of court.) But the State Attorney’s Office eventually cleared both cops of wrongdoing and declared, despite the fact that Reyes was not carrying any weapons that day, the simple act of reaching into his car and grabbing a box was enough to justify getting shot.

Rundle didn’t clear Amores until May 2016 – one month after Rodriguez’s trial. When Rodriguez went to court, records show, Amores was still on prosecutors’ Brady List, a federally mandated record of cops with potential credibility issues. But that evidence never appeared at Rodriguez’s trial.

Via email, Rodriguez’s lawyer with the ACLU, Brandon Buskey, told New Times that his team was unaware Amores had been involved in a prior shooting and had previously been named on the department’s Brady Report list. After New Times informed Buskey, the lawyer said he forwarded the information to Rodriguez’s legal team.

A trained lawyer would have known to use Amores’ history of incidents against him in court. Instead, Rodriguez’s trial was a disaster.

In the 1963 Brady v. Maryland Supreme Court case, justices held that prosecutors must disclose any evidence that could help a defendant at trial. A court transcript obtained by New Times does not contain any evidence that prosecutors told Rodriguez that Amores was still under investigation for the 2013 shooting. If prosecutors did not disclose that information, it’s possible Rodriguez was convicted despite prosecutorial misconduct that could have gotten the case thrown out. (A spokesperson for the Miami-Dade State Attorney’s Office said it could not immediately comment.)

Plus, in 2015, the CIP recommended Amores be placed on its monitoring list after the panel received three complaints about him in a single year. By the time Rodriguez’s trial occurred in 2016, Amores had been sued in federal court by a man who says the cop illegally barged into his apartment without a warrant on behalf of a cab driver who claimed he’d been stiffed on a fare. That case was also settled out of court. (Earlier this year, the Miami Herald further wrote that Amores, now a detective, had botched a 2017 homicide investigation by failing to take basic crime-scene photos and respond to potential witnesses even though a clear suspect existed. The main suspect died by suicide before police were able to arrest anyone for the murder.) As of 2016, city records showed Amores had been involved in eight use-of-force incidents in just four years on the force.

A trained lawyer would have known to use Amores’ history of incidents against him in court. But those traveling through the court system without a lawyer often don’t know how to ask for or obtain that sort of evidence from the state attorneys prosecuting their cases. And, naturally, Rodriguez’s trial was a disaster. A man with a loud voice and a quick temper, Rodriguez stumbled through his defense and repeatedly tried to argue with Amores as he sat on the witness stand – acts that ultimately angered Judge Hague to the point he screamed at Rodriguez.

According to a trial transcript, Hague first noted prosecutors were offering Rodriguez a deal to pay $358 in court fees and fines within a year, accept a charge on his record, and leave that day without jail time. Rodriguez said no. Hague eventually asked if Rodriguez was willing to waive his right to a jury trial and instead let the judge decide his fate in a bench trial.

“I don’t need a jury in front of you,” Rodriguez stated, somewhat confusingly.

Rodriguez then sat as Amores recounted his version of the events during the stop. As Amores finished, it was Rodriguez’s turn to cross-examine the officer -and Rodriguez clearly had no clue what he was doing. At first, he began arguing with the cop about why he had stopped him. After a few statements, Hague lost his patience and cut Rodriguez off.

“No, that’s not the way it works,” Hague stated. “It’s not you say, ‘No, he was actually 1,000 feet away when I said this,’ and ‘He said that.’ That’s you testifying. The question is, ‘How far away was he when this happened?’ ‘Where was he standing?’ ‘What did he do?’ ‘Isn’t it true you were 50 feet from [the] car?’ Whatever it is, but those are questions – not you just testifying as to what you think the facts are.”

“How can I ask a question when the things he is saying are not truthful?” a confused Rodriguez responded. In broken English, he then asked, “What are the questions?”

At this, Hague began to shout.

“I can’t tell you what the questions are!” the judge yelled.

The situation repeated itself for roughly two hours. The state eventually called a different cop to testify: Officer Edward Tobin, who’d been a prosecutor in Broward County for six years before deciding to become a street cop with Miami PD. Tobin testified that Rodriguez got out of his car to chase the cops on foot and yell at them. But when Rodriguez asked Tobin, “Did you see them provoking me?” Hague overruled Rodriguez’s question.

“By the end, the only thing I could do was just cry,” Rodriguez tells New Times.

He says he had resigned himself to paying his fines and living with his criminal record until he got a call in 2017 that the ACLU had been looking for plaintiffs to sue the State of Florida in an attempt to overturn the provision that let Hague strike Rodriguez’s public defender in the first place.

But on February 8, 2018, a federal judge threw out his case. If Rodriguez felt he had been subjected to an unfair trial, the judge wrote, there was already a remedy he could have used: He could have filed his own appeal.