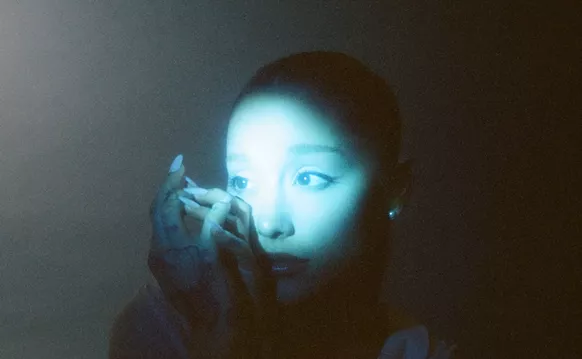

Snail (who plays two concerts in South Florida this week) looks within the subconscious for her particular source of inspiration, gravitating toward the spontaneous, free writing of Jack Kerouac and the dream-based songs of Brian Eno. Just like Eno in the early days, the Philadelphia-born, pale-skinned blonde often appears on stage in glitter makeup and feather boas, accompanied by tape loops, playing electric guitar, and singing wistfully about love and places dreamed of. It's only fitting she would opt for a surreal, inexplicable stage name.

Snail's music stems from a fondness for the exotic and the nostalgic. Her recent solo album, Soft Bloom, features Snail on mellotron, Casio keyboard, zither, kalimba, Moroccan pipe flute, and more. In fact, save a few instrumental contributions from friends, Snail produced all the sounds herself, craftily constructing a heady musical dreamscape. From the opening moments of the first track, "Purr in a Gyre," the otherworldly quality is evident: The guitar shimmers brightly, something that sounds like a cello hums mournfully, and her trusty Moroccan flute flutters like a high-pitched breeze. Halfway through this instrumental opener, the recording suddenly shifts and the mix becomes hazy and muffled, like a curtain being drawn. On "Layton Hollow" Snail uses cymbal rolls and splashes to create a sensation of crashing waves while strumming a slow, rhythmic pattern on a nasal-sounding guitar. Layers of naive melodies pile atop the odd rhythm section, one coming from a cheap, wooden marimba and a couple from her Casio -- one approximating a flute, the other sounding like an air organ. "I see the waters bend and break, break and bend," Snail sings in a patient, dreamy soprano. The album closes with the charmingly simple and all-too-brief, triple-keyboard melody of "Lite Crate," which captures a natural sort of sonic beauty.

A newer Snail release, Staff Party, is a collection of jam sessions with a variety of indie-rock musicians, including keyboardist Chris McDuffie of Denver pop elitists the Apples in Stereo, and Sean Byrne, best known as the mind behind Portland-based experimental pop outfit Bügsküll. The all-instrumental album hums along in a cohesive wash of textures recalling nothing so much as Eno's drifting ambient work.

Collaborations are nothing new to Snail. She's released the results of joint projects with Trumans Water (Stampone) and Susanne Lewis of Hail (Hail/Snail), but she's probably best known for an early-'90s split-single with Sebadoh. "To this day, when people meet me, they say, 'I have that single!'" she states. "A lot of people bought that. It sold thousands and thousands of copies."

A personal eagerness to travel, funded by temp jobs and her modest musical income, has allowed her to perform and release records in Europe. As a result she's made a name for herself on the Continent, producing two exclusive records: the vinyl-only Escape Maker on a British label and Blue Danube, a CD available through a German imprint. Her journeys and connections have allowed her to make friends and jam with the likes of Beck and Low. South Florida is home to another of her favorite partners in crime, Miami's premier noisemonger, Frank "Rat Bastard" Falestra. Whenever Snail visits the area, she says, she never misses an opportunity to "squelch" with Falestra's project, the Laundry Room Squelchers.

Despite her mystic aura and tendency to hold her cards close to her chest, Snail happily shares her early beginnings in songcraft. "I remember my mother kind of forcing me to take piano lessons when I was really young, like six or seven," she says. "At that time your hands are so tiny, and your piano teacher is expecting you to play Mozart and Beethoven. I did all right, but I just remember being frustrated by the whole disciplinary process." That disenchantment led the youngster to the guitar, and thanks to her mom, more lessons. "They expected you to pick out notes and play songs note by note, and you're this little kid, so I was very turned off by the whole technical process of learning how to play an instrument," Snail recalls.

The experience didn't teach her to hate music, but she did feel trapped within the boundaries of what her instructors taught her. Snail recollects a long-lasting lesson she took with her from a music class when she was only ten years old. The teacher had stockpiled an array of instruments from around the world -- "pretty exotic for an elementary school in Maryland," says Snail. "She had all kinds of African and South American percussion instruments, and she would let us pick out whatever we wanted, and we would just jam." A few more uninspired technical classes in music, including theory and chorus, followed, but the jam class made a deep impression on her and would seemingly define her musical aesthetic today. "In retrospect, I was into the jam process immediately, and not the technical process," she adds.

When she was 15 years old, Snail had to find subversive means to acquire an electric guitar because her parents wouldn't consent to one, preferring that she adhere to acoustic instruments only. So she withdrew money from her mother's savings account and took a bus to a nearby music store. When mom arrived home, she was greeted by the power chords and distortion emanating from her daughter's room. "I remember locking my bedroom door, putting this big bureau in front of the door, and just wailing on [my guitar]," she says. "My father was yelling, 'Take that back! You can't have it!' He actually had to take the door off the hinges and forcefully take the guitar away from me. I was crying. It was a very desperate moment for me. I remember telling my mother, 'That's all I want in my life -- this guitar.'"

Unsurprisingly Snail was out on her own shortly after graduating high school, living in New York City, surviving by temping at various offices, and nourishing her talents through the support of local musicians. By the late '80s, Snail was receiving airplay on Low-Fi, a specialty show aired by New York's WFMU-FM and hosted by DJ William Berger. Granted, it wasn't very difficult to get a recording on the program. "You could make recorded music at home on a Tuesday, send it to Bill that day, and he'd play it on his show on a Friday," she explains. Berger quickly became a fan, and after Snail found the courage to perform, her skills were soon noticed by others. Following her second-ever live performance, the small, independent Albertine Records offered to release her debut recording, a single entitled "Another Slave Labor Day." Albertine subsequently issued her first album, Snailbait, in 1989, and since then she's bounced back and forth -- no major label has shown interest, she admits, but indie imprints have been eager to affiliate with her, and so the remainder of Snail's '90s output is scattered among different companies around the globe.

The result has been the creation of an obscure artist, well beneath the public radar but respected by other musicians, an arrangement that seems to suit Snail. As enigmatic as she appears in person, she still apologizes for her pretensions. "I've always not liked the mainstream," she says. "I tried to discuss that with friends of mine: Why do some people accept the mainstream and others want to delve into the most obscure things they can find? I don't know. I just love what I love."